Caliber of the Month: 25 Auto

The Case for the .25 Auto: Deep Concealment, Shootability, and Honest Tradeoffs

- The .25 ACP is often dismissed, but it still fills a niche where deep concealment matters most.

- Designed by John Browning, it prioritizes reliability, low recoil, and ultra-compact pistols.

- Ballistically modest, it can’t compete with modern duty calibers like 9mm or .380 ACP.

- Its strengths are controllability, shootability, and concealability—not stopping power.

- With realistic expectations, solid shot placement, and consistent training, it remains viable for close-range defense.

In a world dominated by high-capacity, polymer-framed pistols chambered in 9mm Luger, the humble .25 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) often gets dismissed as a novelty that's best left to antique collectors and noir film protagonists. But with that line of thinking, you're really leaving money on the table. Sure, it's not as impressive as 9mm Luger, .40 S&W, or even .45ACP. But does it really have to be to still hold its own as a defensive cartridge?

The .25 Auto is unique, no doubt. It’s small, relatively mild in terms of recoil and “stopping power,” and it can be a little hard to find at times. Yet, it maintains a cult-like following. Some might say it's even had a bit of a renaissance in recent years. Either way you look at it, the .25 Auto was designed specifically for pocket carry pistols, delivering reliable performance while maintaining a sleek profile for super-deep concealment.

And while the .25 Auto isn't exactly a modern ballistic superstar, in the realm of “deep cover” pocket pistols, it remains a practical answer when size and absolute concealment trump outright terminal performance.

A Brief History of the .25 Auto

One of John Browning's many revolutionary designs, the .25 Auto was introduced in 1905 alongside its companion firearm, the Fabrique Nationale (FN) Model 1905 pistol, later produced as the Colt Model 1908 Vest Pocket. Browning's goal was to create a reliable, centerfire alternative to the .22 rimfire cartridges of the era, which were notoriously unreliable in semi-automatic actions.

The semi-rimmed case design of the .25 Auto ensured smoother feeding and extraction in compact, blowback-driven pistols. Its development coincided with a period when discreet personal defense options were in high demand. For decades, the round served plainclothes police officers, civilians, and anyone who needed a firearm that could vanish into a coat or pocket.

Over time, however, the .25 ceded popularity to larger, higher-performing, and more modern handgun rounds, but the platform's simplicity, small footprint, and manageable recoil have kept it alive in the modern market for micro-pistols and specialized carry guns.

A Case for the .25 Auto

The .25’s claim to fame is concealability and shootability. Firearms chambered in .25 ACP are among the smallest and lightest semi-automatic pistols ever to hit the market, making them easier and more comfortable to carry in situations where larger guns are simply impractical. Think of tucking a pistol into the waistband of gym shorts (not my jam, but to each his own), carrying discreetly in formal wear, or slipping one into a pocket for a quick trip to the store. In these deep concealment scenarios, a .25 Auto pistol is likely going to be a better option than your Glock 19. At least in terms of concealment.

Ballistic Performance and Practical Limits

As a target shooting or training tool, the .25 Auto is a solid choice. The low recoil allows users to focus on sight alignment, trigger control, and smooth follow-through without that ever-annoying recoil-induced flinch.

But as a defensive round, the .25 Auto is, by any modern measure, a modest performer. If you can comfortably carry anything bigger, such as a micro-compact chambered in .380 ACP or 9mm, those rounds will usually be better defensive choices. Obviously.

A typical .25 ACP load fires a 50-grain Full Metal Jacket (FMJ) bullet at a velocity of approximately 760 feet per second (fps), generating around 64 foot-pounds of muzzle energy.

To put that in perspective, a standard velocity .22 LR from a pistol barrel will deliver similar energy, while a typical .380 ACP cartridge produces between 150 and 200 foot-pounds of energy, more than twice that of the .25 Auto.

Still A Viable Option

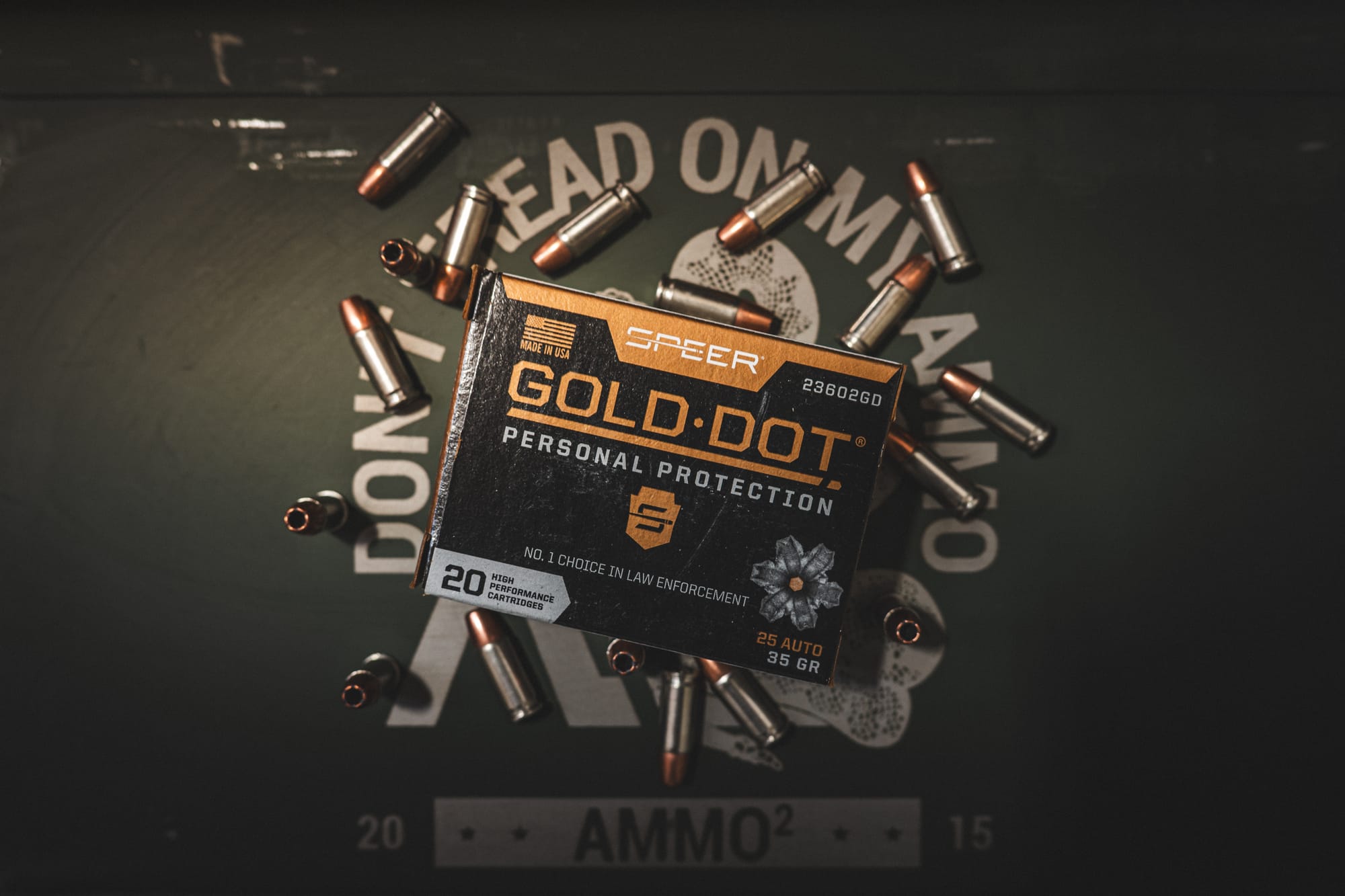

The primary challenge for the .25 Auto is achieving adequate penetration to reach vital organs, especially after passing through heavy clothing. Hollow-point ammunition, while theoretically beneficial, often struggles to expand at these low velocities, frequently acting like a standard FMJ projectile anyway. This means shot placement and consistency are everything with the .25 Auto.

Where the .25 earns its keep, though, is in controllability and reliability (on well-maintained pistols). In a defensive scenario where distance is inside five to seven yards and concealment is a hard constraint, a well-delivered shot on target can be superior to no gun at all, provided you accept the tradeoffs.

So despite its obvious shortfalls, the .25 Auto is still more than viable as a training and defensive round. Train aggressively and realistically. Your goal is to overcome the round's power deficit with speed and accuracy. This means practicing rapid-fire strings to deliver multiple rounds on target quickly, and proven drills, like the Mozambique Drill (two shots to the chest, one to the head), are a necessity. Relying on a "one-shot stop" is a dangerous fantasy with any handgun caliber, but it's especially unrealistic with the .25 Auto.

Final Thoughts

The .25 Auto is no ballistic powerhouse. It cannot compete with modern duty calibers. But to dismiss it entirely is to ignore its core design genius and seemingly perfect combination of concealability, low recoil, and simplicity.

If your carry plan demands the smallest possible footprint and you accept the ballistic compromises, the .25 ACP can still be a defensible choice. A few well-placed shots from a .25 in your pocket is infinitely more effective than nothing at all. But recognize its limits, practice often, choose reliable ammunition (often high-quality FMJ for penetration), and treat it as a last-resort tool designed for close-range encounters.

That said, specialty ammunition supplies can be unpredictable. If you're thinking of adding a classic .25 Auto to your collection or carry rotation, plan ahead. Log in to your AmmoSquared account today to ensure your supply is well-stocked and ready for when you need it most.